Elon Musk is going to keep blowing your mind

Tippets by Taps #143: Elon Musk, the Polymath Playbook, American passports, and more. Enjoy!

Welcome to the 9 new Tippets readers who have subscribed over the past week! A big thank you to those of you who shared the newsletter. If you're reading this, not yet subscribed, and looking to receiving Tippets alongside the other similarly curious, intelligent people who've already subscribed, click below! 😄

Whether you love him or hate him, you have to give him credit: the man makes the impossible, possible. He’s established dominance in the streets with Tesla, dominance in outer space with SpaceX, and currently working the underground with The Boring Company. He’s doing more at once than most people do in their lifetimes.

I thought this observation about Musk was quite astute:

The physical nature of Musk’s work is incredibly compelling. Most people (even those working in technology) don’t know or understand how hard it is to build and scale the software experiences that we take for granted every day (side note: for all my tech worker subscribers, say thank you to your DevOps team). With the right idea and a good enough sketch on the back of a napkin, you too can become the next technology millionaire, right? How many times have you read about a company or app that has received VC investment or been acquired and thought to yourself, really?

The intangible nature of bits and bytes (unfortunately) makes it easier to dismiss the complexities and challenges of building a successful software company. The opposite is true about building a hardware and manufacturing company. Everyone intuits that building a car is hard. Everyone knows building a rocket is hard (after all, everything else is is 'not rocket science’).

That’s what’s so unique about Musk. Building new and innovative versions either a car or a rocket? Hard. Becoming the market leader in the field? Hard. Doing both at the same time?

This week the New York Times published an insightful and quite funny interview between Musk and Maureen Dowd. Well worth the read, they discussed a range of subjects, from Twitter and relationships to Facebook and competition with Jeff Bezos. However, I thought the below snippet was the most interesting:

[His friends] describe his internal narrative as going something like this: “I’m going to take over the world. That’s going to be a super-crazy process. And therefore, if the roller coaster ride isn’t incredibly scary, I’m doing something wrong.”

Musk is as close to a real-life Tony Stark as it gets. A polymath by any reasonable definition, despite (or more likely thanks to) his eccentricities, quirks, and behavior uncommon to other occupants of the world’s richest people list, he has captured the world’s attention. The crazy thing? For Elon, the world isn’t enough.

Further Elon reading:

Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future by Ashlee Vance

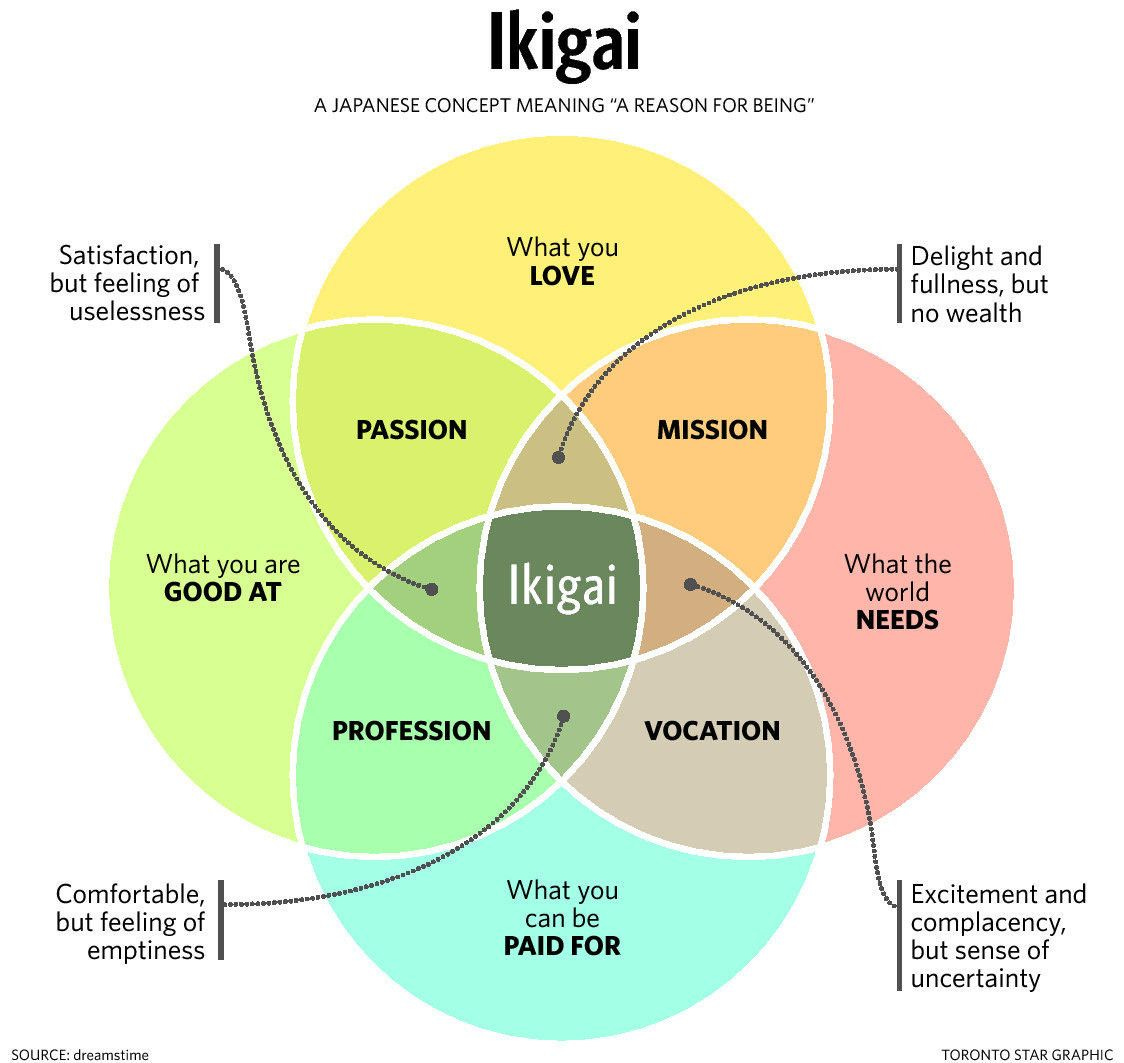

The Polymath Playbook

As the global economy has unfolded over the last 50 years, specialization has become the name of the game. Basic laws of economics suggest that increased specialization leads to greater economic output which in turn leads to increased societal benefit. At the individual level, the more specialized I am, the fewer people there are that can do what I do, which in turn means my value in society goes up (assuming, of course, I have specialized in something people want). Specialization makes total sense right?

In this post, Salman Ansari argues that specialization limits adaptability and, in fact, more people should aim to be polymaths, able to pull from various fields in order to “develop mental models from different fields and apply them to solve problems in a unique way.”

A well-written piece with great personal anecdotes, it helped articulate for me some of the reasons why I have gravitated toward roles that have been more horizontal and multi-functional in my career as I continue my search for ‘ikigai’.

The Declining Power of the American Passport

The American passport has, for the better part of the last 75 years, been the key that unlocks global exploration. Prior to the pandemic over 100 countries were willing to admit US citizens if they simply flashed their blue, eagle emblazoned papers. Post pandemic, due to the failure of the country to contain the spread of the virus, this number is as low as 30.

As a Canadian citizen (172 countries open without a visa) of Indian origin with a parent that still holds an Indian passport (58 countries open without a visa), I know all too well how equalizing the immigration line can be. While the plight of US citizens is likely to reverse once the pandemic passes, for a brief moment US citizens are now aware of the restrictive feeling that this article articulates so well.

There is an inherent randomness—some would reasonably call it unfairness—in how the world enforces the idiosyncrasies of travel and immigration. Through circumstance, you are born in a place, and the history and the policies of that place will, for the majority of humanity, forever determine whether, to where, and for how long you can leave.

American citizens have mostly been spared the stress and humiliation of this universe: An American passport, until recently, could bring you anywhere with minimal need to worry about visas and border checks.

Perhaps you, too, will fervently follow news of progress on visa liberalization, which your country has made a priority in trade negotiations. Perhaps you, too, will make sure to shave the morning of a flight, worried that the combination of facial hair, brown skin, and a foreign passport will inspire some immigration officer to “randomly” select you for additional questioning

The Confessions of Marcus Hutchins, the Hacker Who Saved the Internet

This is the sub-head for this long read:

At 22, he single-handedly put a stop to the worst cyberattack the world had ever seen. Then he was arrested by the FBI. This is his untold story.

If you can spare an hour, read the story that still hasn’t arrived at its conclusion. If not, you can wait for the movie. It’s got to become one.

Work Alone: Ernest Hemingway’s 1954 Nobel Acceptance Speech

I stumbled across Ernest Hemingway’s Nobel Acceptance speech this week. Short and to the point, it follows Hemingway’s iceberg theory, with messages hidden between the lines.

Writing, at its best, is a lonely life. Organizations for writers palliate the writer’s loneliness but I doubt if they improve his writing. He grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness and often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day.

For a true writer each book should be a new beginning where he tries again for something that is beyond attainment. He should always try for something that has never been done or that others have tried and failed. Then sometimes, with great luck, he will succeed.

Quote I'm thinking about: “A jack of all trades is a master of none, but oftentimes better than a master of one.”

If you have feedback on anything mentioned above or have interesting links/papers/books that you think would be worth sharing in future issues of Tippets, please reach out! Reply to this email, click the feedback link below, or DM me on Twitter at @taps.